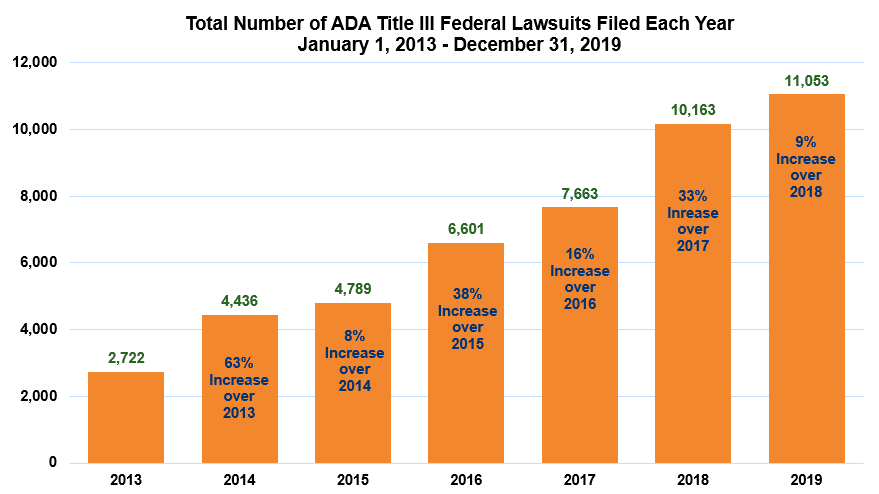

If you work for a business with an online storefront, or if your company has been implementing accessibility into its online services, then it’s likely that you have heard of the ADA. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is the primary driver of accessibility-related litigation against U.S. businesses; in 2019 there were 11,053 lawsuits filed under ADA Title III. These filings increased 9% over the 10,163 lawsuits filed in 2018, which was an increase of 33% over the previous year. In order to get ahead of these lawsuits it is important to understand how U.S. courts interpret Title III of the ADA and how to comply with its legal technical standards.

The ADA is founded on the basis of civil rights. Without the protections extended by accessibility regulations, people with disabilities would be excluded from places of employment, public spaces, communication and information access. The express purpose of the ADA in federal law, therefore, is “to provide a clear and comprehensive national mandate for the elimination of discrimination against individuals with disabilities.” In particular, Title III of the ADA addresses places of public accommodations and commercial facilities. There are 12 categories of places of public accommodation under the ADA, such as restaurants and bars, public transportation terminals, educational institutions, and hotels. Title III is the reason you have seen Braille placards outside of every public bathroom built since the ADA’s passage in 1990.

But what do Braille placards, wheelchair ramps and accessible bathroom stalls have to do with website accessibility? This is the question that has been in contention for almost a decade, ever since e-commerce websites and apps began to supplant brick-and-mortar retailers.

Places of Public Accommodation in the ADA

The first landmark case to question the applicability of “places of public accommodation” in the ADA to websites was the 2006 case of National Federation of the Blind v. Target Corporation. The ADA prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability “in the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages or accommodations of any place of public accommodation.” In the suit, Target argued that the adduced civil rights laws (California Unruh Civil Rights Act, California Disabled Persons Act, and ADA) were intended to apply only to retail stores, and not to a company’s online activities. According to the case ruling, however, “the statute [Title III] applies to the services of a place of public accommodation, not services in a place of public accommodation. To limit the ADA to discrimination in the provision of services occurring on the premises of a public accommodation would contradict the plain language of the statute.” The Department of Justice has backed up the Target decision by repeatedly affirming the application of Title III to websites of public accommodations.

Title III applies to discrimination in the goods and services ‘of’ a place of public accommodation, rather than being limited to those goods and services provided ‘at’ or ‘in’ a place of public accommodation.

The NFB v Target ruling seemed to establish in clear terms that Title III applies to the accessibility of online retailer’s websites, and it was followed by thousands of class action lawsuits and individual filings based on this conclusion. Although the interpretation of Title III seemed clear, however, lawsuits before and since Target have fixated on a crucial question that still does not have a unanimous consensus: What if there is no physical space?

A “Nexus” Between Storefront and Website

In 2002 a district judge in Florida ruled in favor of Southwest Airlines’ motion to dismiss an ADA Title III complaint, based partly on the grounds that the plaintiff had not established a “nexus” between the Southwest.com website and a physical, concrete place of public accommodation. In other words, the plaintiff failed to show that Southwest’s website was a gateway to Southwest’s physical store locations.

This “nexus” requirement is increasingly problematic in the 21st century, as we have entered a world in which many retail establishments operate solely online without any physical, brick-and-mortar locations. It brings our 21st century world in conflict with the ADA’s 20th century language of a “physical space.”

When Winn-Dixie faced a lawsuit in 2017 from a blind plaintiff, it was clear from the testimony that Winn-Dixie’s website was inaccessible to visually impaired individuals. However, the case questioned whether the Winn-Dixie website was sufficiently integrated with Winn-Dixie’s physical store locations that its inaccessibility would deny the plaintiff full and equal enjoyment of the store’s goods and services. The court found that accessibility barriers in the website’s store locator feature and prescription ordering service for in-store pickup established a nexus between Winn-Dixie’s website and its physical stores.

U.S. courts of appeals are split with regards to whether Title III requires the plaintiff to establish a nexus between a store’s online properties and its physical locations. Courts in the Third, Sixth, Ninth and Eleventh Circuits have maintained that only businesses with a nexus to a physical location are subject to the ADA. In opposition, Courts in the First, Second and Seventh Circuits do not include the “nexus” requirement in their interpretation of Title III. In a lawsuit against art materials supply store Blick, Judge Weinstein of the Second Circuit characterized the “nexus” interpretation of Title III to be “narrow” because it means that “a business that operates solely through the Internet and has no customer-facing physical location is under no obligation to make [its] website accessible.”

The nexus requirement brings our 21st century world in conflict with the ADA’s 20th century language of a ‘physical space.’

The opinion of Judge Weinstein is likely to be replicated in future Title III cases, and it would not be surprising if circuit split were to resolve itself against the “nexus” requirement. As we see more and more retail establishments operating solely online, it makes no sense to exempt retailers such as Amazon, hotels and airlines from Title III of the ADA, as accessibility barriers to their websites are made even more exclusionary by their absence of physical retail outlets.

In summary, the number of federal filings of Title III cases is only likely to increase, and the more liberal definition of a “place of public accommodation” is only likely to expand and include websites for online retailers as well as brick-and-mortar stores. If your business does engage in e-commerce, the best strategy is to proactively ensure the accessibility of your websites and mobile applications. In all of the Title III case rulings covering retailer websites, courts have referred to the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) Levels A and AA as the benchmark for legal compliance.

References

- The Muddy Waters of ADA Website Compliance May Become Less Murky in 2019

- 42 U.S. Code 12101 Findings and Purpose – Cornell Law

- 2019 CSUNATC Digital Accessibility Legal Update – Lainey Feingold

- National Federation of the Blind v. Target Corp – Leagle

- Two New York Federal Judges Refuse to Dismiss Website Accessibility Cases – JD Supra

- Florida Courts Rule ADA Covers Websites with Nexus to Physical Store – Seyfarth

- Federal Judge Holds Grocery Store Website Subject to ADA – Ballard Spahr

- Statement of Interest filed by the United States against Winn-Dixie Stores – ADA.gov

- Access Now, Inc. v. Southwest Airlines, Co. – Justia US Law